Aliette nos ha permitido reproducir aquí el primer capítulo de libro, para que la espera sea aún peor:

Chapter One

The Falling Star

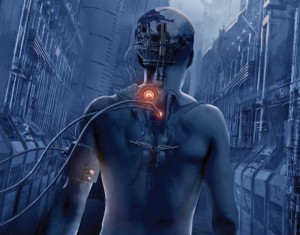

It is almost pleasant, at first, to be Falling.

The harsh, unwavering light of the City recedes, leaving you in shadow, leaving only memories of relief, of a blessed coolness seizing your limbs. Nothing has turned yet into longing, into bitterness, into the cold that will never cease, not even in the heat of summer.

The wind, at first, is pleasant, too—softly whistling past you, so that you almost don’t notice when its cold fingers tear at your wings. Feathers drift off, blinking like forgotten jewels, catching fire and burning like a thousand falling stars in the atmosphere. Some part of you knows you should be experiencing pain; that the flow of crimson blood, the lancing pain in your back, the fiery sensation that seems to have hold of your whole body—they’re all yours, they’re all irreversible and deadly. But you feel nothing: no exhilaration, no relief, not the searing agony of your wounds. Nothing but that sense of unnamed relief, that knowledge you won’t have to face the judges in the City again.

Nothing, until the ground comes up to meet you, and you land in a jumble of pain and shattered bones; and the scream you didn’t think you had in you scrapes your throat raw as you let it out—like the first, shocked breath of a baby newly born into a universe of suffering.

***

It was Ninon who first saw her. Philippe had felt her presence first, but hadn’t said anything. It wasn’t a wish to protect the young Fallen so much as to protect himself—his status in the Red Mamba Gang was precarious as it was, and he had no desire to remind them how great a commodity he could become, given enough cruelty on their part. And Heaven knew, of course, that those days it didn’t take much for cruelty or despair to get the better of them all, when life hung on a razor’s edge, even for a former Immortal.

They’d been scavenging in the Grands Magasins—desperate and hungry, as Ninon had put it, because no one was foolish enough to go down there among the ruins of the Great Houses War, with spells that no one had had time to clean up primed and ready to explode in your face, with the ghosts and the hauntings and the odor of death that still hung like fog over the wrecks of counters and the faded posters for garments and perfumes from another, more innocent age.

No one, that is, but the gangs: the losers in the great hierarchy, the bottom feeders surviving on the carrion the Houses left them. Gangs could be huge, could number dozens of people, but they were fractured and powerless, deprived of the magic that made the Houses the true movers of Paris. And as far as gangs went, the Red Mambas were small; twenty or so members under Bloody Jeanne’s leadership; and Philippe, on the bottom tier of the bottom tiers, just doing his best to survive—as always.

He and Ninon had been under the dome of the Galeries Lafayette, crossing over the rubble in the center—what had once been the accessories department. On the walls were fragments of advertisement posters, colored scraps; bits and pieces of idealized human beings, of products that had long since ceased to be manufactured; and a fragment promising that the 1914 fashion season would be the headiest the city had ever seen: a season that, of course, had never been, swallowed up by the beginning of the war. Ahead were the stairs, blocked by debris; the faces of broken mannequins stared back at them, uncannily pale and expressionless, their eyes shining like cats’ in the dim light.

Philippe hated the Grands Magasins—not that he was as superstitious as Ninon, but he could feel the pall of death hanging over the place, could almost hear the screams of the dying when the petrification spells had struck. Like any Immortal—even a diminished one, far from his home and his people—he could feel the khi currents, could sense their broken edges rubbing against him, as sharp as serrated knives.

“Ninon—”

Ahead, on the stairs, she’d turned back at him, her face flushed with the excitement of it all, that incomprehensible desire to flirt with danger until it killed you. A wholly human thing, of course; and he was meant to be human again, now that he had been cast out of the Heavens; but even as a mortal in Annam he’d just never had that kind of reckless death wish. “We should go—” he’d started, and then he’d felt it.

It was pure and incandescent, a wave of stillness that seemed to start somewhere in his belly and spread to his entire body—a split second when wind ran on his arms and face, and darkness stole across his field of vision, as if night had unexpectedly fallen in the world beyond the dome; and a raw sense of pain rose in him, a scream building in his lungs, on the verge of forcing its way out . . .

And then it was gone, leaving him wrung out, panting on the staircase as if he’d just run for his life across Paris. The pain was still at the back of his mind—a faint, watered-down memory that he would recognize anywhere—just as he would unerringly be able to find its source.

A Fallen. A young one, barely manifested in the world, lying in pain, somewhere close; somewhere vulnerable in a city where young Fallen were merchandise, creatures to be taken apart and killed before they became too powerful and did the taking apart and the killing.

“You okay?” Ninon asked. She was watching him, eyes narrowed. “Not going to go all mystical on me, are you?”

Philippe shook his head, struggling for breath—couldn’t show weakness, couldn’t show ignorance, not if he wanted to survive . . . At last he managed, in something like his usual flippant tones, “No way, sis. This is about the worst place in the world to get an attack of the mystical.”

“Doesn’t mean you idiots wouldn’t get one,” Ninon said, darkly. “Come on. Alex said there was good booty on the third floor, perfumes and alchemical reserves.”

The last thing Philippe wanted to do was go upstairs, or hang around the place any longer than he had to. “And they’ve remained miraculously untouched for sixty years? Either Alex is misinformed or there’s some pretty heavy defenses. . . .”

Ninon grinned with the abandon of youth. “That’s why we have you, don’t we? To make short work of anything.”

“Sure,” Philippe said. He could cast some spells; call on some small remnants of who he had been, drawing from the khi fields around him. He would, however, have to be seriously insane to do it here. But he daren’t protest too much, or too loudly; he was, as Ninon had reminded him, only useful as long as he could provide magic—the conscious, mastered kind, one cut above the lures of angel essence and other adjuncts. When that ceased . . .

He forced himself not to think about it as he followed her upstairs—past landing after deserted landing, under the vacant eyes of models in burned posters, past the tarnished mirrors and the shards of chandeliers. As he had feared, the pain at the back of his mind grew steadily, a sign they were approaching the Fallen’s birth site. Ninon herself wasn’t a witch—the magical practitioners had long since been snapped up by the Houses—but for all that, she was uncannily, unerringly headed toward the newly manifested Fallen. “Ninon—” he said, as they rounded a ruined display promising exotic scents from Annam and the Far East, a memory of a home that was no longer his.

Too late.

She’d stopped, one hand going to her mouth. He couldn’t tell what her expression was, from behind, if it was horror or fascination or something else. As Philippe got closer, he saw what she saw: a jumble of crimson-stained feathers, a tangled mass that seemed to be all broken limbs and bleeding wounds; and, over it all, a gentle sloshing radiance like sunlight seen through water, a light that promised the soft warmth of live coals, the comfort of wintertime meals heated on the stove, the sheer relief just after the breaking of a thunderstorm, when the air was cleansed of all heaviness.

Philippe recovered faster than Ninon. While she still stood, gaping at the vision, he cautiously approached, circling the body with care, just in case the Fallen turned out vicious. But Philippe didn’t think it would.

Close up, the body was a mess: bones broken in several places, not always cleanly; the hands splayed out in abandon, loosely resting above dislocated wrists; the torso covered with blood and unidentifiable fluids. There was no smell, though; no stench of blood or ruptured guts; just a tang to the air, an acridity like a remnant of burning wood. Young Fallen never smelled like much of anything, not until the light vanished. Not until they joined the mortal plane like the rest of their kind.

The face . . . the face was intact, and that was almost the most gruesome thing about the Fallen. Eyes frozen in shock stared at him. The gaze was somehow ageless, that of a being that had endured beyond time, in a City that had nothing human or fragile about it. The cheekbones were high, and something in the cast of the face was . . . familiar, somehow. Philippe glanced back at the mess of the torso, noting the geometry of the chest: this particular Fallen manifested as female.

He hadn’t expected to be so . . . detached about things. He’d thought of a thousand ways she could have reminded him of the Great War, of the bloodied bodies by his side; but in some indefinable way she seemed beyond it all, a splayed doll rather than a broken body—he shouldn’t think that, he really shouldn’t, but it was all too easy to remember that it was her kind that had torn him from his home in Annam and sent him to slaughter, that had gloried in each of the dead, that had laughed to see his unit come back short so many soldiers, covered in the blood of their comrades—her kind, that ruled over the ruins of the city. . . .

“Awesome,” Ninon said. She knelt, her hands and arms bathed in the radiance, breathing in the light, the magic that hung coiled in the air around them. Fallen were magic: raw power descended to Earth, the younger the more powerful. “Come on, help me.”

“Help . . . ?”

Ninon’s hand flicked up; it came up with a serrated knife, the wickedly sharp blade catching the light.

“Can’t carry her. Too much work, and there’s only two of us. But we can take stuff.”

Stuff. Flesh and bone and blood, all that carried the essence of a Fallen, all that could be inhaled, put into artifacts, used to pass on magic and the ability to cast spells to others. He put his hand in the blood, lifted it to his mouth. The air seemed to tremble around his fingers as if in a heat wave, and the blood down his throat was as sweet as honey, warming his entire body, reminding him how it had been when he’d been an Immortal; and a flick of his hands could have transported him from end to end of Indochina, turned peach trees into magical swords, turned bullets aside as easily as wisps of vapor.

But that time was past. Had been past for more than sixty years, turned to dust as surely and as enduringly as his mortal family.

Ninon’s face was bathed in radiance as she knelt by the body—she was going for a hand or a limb, something that would have power, that would be worth something, enough to sustain them all . . . It— the thought of her sawing through flesh and bone and sinew shouldn’t have made him sick, but it was one thing to hate Fallen, quite another to cold-bloodedly do this.

“We could take the blood,” he said, forcing his voice to come back from the distant past. “Use the old perfume bottles to mix our own elixirs.”

Ninon didn’t look up, but he heard her snort. “Blood’s piffle,” she said, lifting a limp, torn hand and eyeing it speculatively. “You know it’s not where the money is.”

“Yes, but—”

“What’s the matter? You feeling some kind of loyalty for your own kind?”

She didn’t need to make the threat, didn’t need to point out he was as good a source of magic as the Fallen by her side.

“Come on, help me,” she said; and as she lifted the knife, her eyes aglow with greed, Philippe gave in and pulled his own from his jacket; and braced himself for the inevitable grinding of metal against bone, and for the Fallen’s pain to paralyze his mind.

***

Selene was coming home to Silverspires when she felt it. It was faint at first, a chord struck somewhere in the vastness of the city, but then she tasted pain like a sharp tang against her palate.

She raised a hand, surprised to find she’d bitten her tongue; probed at a tooth, trying to see if the feeling would vanish. But it didn’t; rather, it grew in intensity, became a tingling in the soles of her feet, in her fingertips—a burning in her belly, a faint echo of what must have been unbearable.

“Stop,” she said.

There were four of them in the car that night: two of her usual guards, Luc and Imadan, and Javier, the Jesuit, the latest of several incongruous additions to the House. He had volunteered when Selene’s chauffeur fell ill. She’d found him in the great hall, stubbornly waiting for her, his olive skin standing out against the darkness of his clothes; and had simply gestured him into the car. They’d hardly spoken a word since, and Selene hadn’t probed. Like the rest of the motley band that constituted the House, Javier would open in his own time; there was little sense in trying to nudge or break him open—God knew Selene had had enough experience, by now, of what it meant to break people. Morningstar had taught her well, from beginning to end.

“What is it?” Javier asked.

Selene raised a hand to silence him, seeking the origin of the magic. Young, and desperate; she’d almost forgotten how that tasted, how bittersweet it all was, that mixture of bewilderment and pain that came just after the Fall.

West, in the ruined blocks that had been the great department stores and the great hotels before the war, their names like a litany of what had been lost: the Printemps, the Galeries Lafayette, the Hôtel Scribe, the Grand Hôtel . . . West, where the House of Lazarus still stood. And if she could feel it, so could every other Fallen in the vicinity; and perhaps their pet mages, too, if they had the right artifacts or were pumped up on essence.

Needless to say, Selene did not approve of essence.

“We don’t have much time,” she said to Javier. “It’s an infant Fallen, and it’s in trouble.”

Javier’s face was pale, but set. “Tell me where.”

“Right,” Selene said. “Left at the next intersection.”

The car moved smoothly under Javier’s hands—though of course there was nothing smooth about it, and the battered and old metal carcass ran as much on magic as it did on expensive fuel.

Left, straight ahead, right, left. It was in her bones now, a dull vibration, a vague hint of something red-hot and searing, something that would overwhelm her, given half a chance.

Ahead was the dark mass of the Galeries Lafayette: the dome had miraculously survived the war and everything thrown at it, but the insouciant crowds that had once filled the shops at the beginning of the twentieth century, marveling at hats and brocade robes, sitting in droves in the tearoom and reading rooms, were all gone. It had been sixty years, and none but the insane would enter the Galeries now.

The insane, or the powerful.

“Park here,” Selene said, pointing to a somewhat clear space among the rubble. She glanced at the shadows; there were people there, the lost and the Houseless, but they wouldn’t move unless Selene showed weakness of some kind. Which wouldn’t happen. She was old enough by now to know the rules of the city, and not foolish enough to leave her car unprotected. Anyone who attempted to open it after they were gone would get a nasty shock as a warning, and incineration if they persisted.

“Here?” Javier asked, slowing.

“Yes. Come on, there isn’t much time.” She could feel the pain and the fear, the way they were building up, faster and harder than they should have.

Which meant only one thing.

Someone was trying to hurt the Fallen. In her city, within her reach.

She didn’t think. Without pausing to check if Javier was following, she strode under the dome and onto the vast stairs, vaguely feeling rubble shift and crumble under her feet. The pain and the need were within her, rising—a sharp, short stab followed by agony that would have doubled her over in pain, but her wards took the brunt of it, leaving only anger, only fear. . . .

Magic was building within her—drawn from the House, from the city and its river blackened by ashes, from the devastated countryside that surrounded them all beyond the wastelands of the Periphérique, layer after layer of gossamer-thin spells, not as powerful as they had once been. But she was old and canny, and forged into a weapon by her master, Morningstar, and what she’d lost in power she more than amply made up in skill. The pain in her mind receded, to be replaced by white-hot anger; so that, by the time she reached the third floor and saw, among its shattered counters, the two people crouching in the unbearable radiance of a newly manifested Fallen, her thoughts were as clear and as sharp as glass blades.

“You will stop,” she said in the silence.

They looked up, both of them: a girl no older than fifteen or sixteen, her face coated with grime, her malnourished frame making her seem even younger; and a boy of perhaps twenty, dark-skinned, narrow-eyed—an Annamite, by the looks of him—and then she saw the blood splayed on their hands and on their clothes; and the blades they’d been using to saw two fingers loose from the Fallen’s shattered hand.

That was the fear she had felt—waking up, fuzzy and disorientated after the Fall, still struggling to adjust to a bewildering world; and finding only pain and the slow, excruciating sawing of a knife against her hand. . . .

“You will stop,” Selene said again, coldly. “Now.”

The girl laughed. Her lips were stained with blood and her high-pitched voice was all too familiar, the voice of someone drunk on strange and unaccustomed power. “Or what? You’ll make me? I don’t think you can. You’re old and scarred and the magic doesn’t sing to you anymore.”

“Ninon—” the boy said—no, not a boy. Selene had been mistaken; he must have been older, twenty-five or thirty. He was breathing heavily, his pupils dilated; but apart from the blood, nothing about him indicated he’d consumed the flesh of the Fallen. Or perhaps he was merely more experienced. Either way, she was the real danger: the leader, the hothead.

Selene threw a thread of magic, intending to pick up the girl and fling her aside from the prone Fallen—but Ninon laughed, and the power buried itself among the shards of glass from perfume bottles.

“Told you,” she said. “My turn.”

What she sent snaking toward Selene was brutal, undiluted, with the potency of a wildfire, its heat as scorching as the naked sun—and somewhere in its heart was the pain and hurt and betrayal of being cast out from the City, as raw as open wounds. Selene had to take a step back while she wove and rewove furiously, knitting her wards so that the magic, instead of shattering them, was guided until it buried itself into the floors of the Galeries.

Fallen blood. Fallen magic. Stolen magic, hacked away in a rush of pain, the same pain that was now at the back of her mind like a coiled snake.

That upstart girl would never steal again.

The young man was tugging at Ninon’s sleeve now, his face twisted in panic, though Selene could still hear his exhausted panting. “Please. You can’t go up against her. Not for long. She’s House, Ninon.”

Ninon turned and threw him a withering glance, opening her mouth for some scathing retort. Selene didn’t wait. She gathered all that she could, pulling in from the ghosts of the Grands Magasins, from Silverspires and the throne where Morningstar had once sat, from the mirrors and water basins where witches strove to recreate glimpses of the City—and sent it, not toward Ninon, but toward the floor. It left her hands, a barely distinguishable tremor, a pinpoint that became a raised line, and then a rift across the faded ceramics tiles that would tear the girl apart.

She had no pity. Not tonight, and certainly not for people who fought for the right to dismember Fallen as if they were cattle.

Too late, Ninon saw it. She turned away from the young man and, raising her hands, tried to absorb the magic as Selene had done. But she was untrained; and the light of the magic left her face, the little flesh and blood she’d consumed burning like wastepaper in a hearth—her face twisted as she realized that she didn’t have power anymore, that she didn’t have time to find more, that it was going to hit whatever she did. . . .

“Get out!” Ninon screamed to the young man, in the split second before the rift was upon her.

There was no time left. None at all, and the young man was still there by her side as the rift hit, and the light flared so brightly that even Selene had to avert her eyes. She braced herself for the impact, for the wet sound of bodies twisted past endurance, for the gouts of blood to join the Fallen’s on the floor.

Instead . . .

It was like nothing she’d ever felt: a stillness, a quiet like the eye in a storm, a slow, delicate weaving that drew, not on the ghosts, not on the City, but on something else entirely. The rift stopped, inches from the young man, who stood with his hands open and sweat glistening on his face, his hair raised on his scalp. For a moment—a brief, sharp moment that etched itself indelibly in Selene’s mind—he seemed to hold the weight of her spell in his hands, the whole of her fury and her anger—and then he opened his hands and it was gone, harmlessly snuffed out.

A witch, here? Why hadn’t he—?

She had little time for introspection. Time seemed to resume its normal flow; the young man crumpled like a puppet with cut strings, lying bathed in the Fallen’s radiance. The girl, Ninon, stood for a moment, looking at him, looking at Selene; and then she spun on her heels and ran.

Selene made no movement to stop her. Ninon was hardly worth the trouble, and in any case it was all she could do to stand.

“You’re a fool,” Javier said gruffly, coming up behind her.

“You felt it?”

Javier shook his head as he moved to survey the wreckage. “Credit me with a little perception. You can’t draw on this much power and hope it’ll suffice to end fights. You usually don’t get a second chance of casting that kind of spell.”

“With amateurs, it usually suffices,” Selene said absentmindedly. She looked at the young man again. There was nothing special about him, no tremor of recognition racing up her arms. He was clearly no Fallen. But no witch—even high on angel essence, even with the most powerful artifacts of a House at her disposal—should have been able to do anything like this.

Her gaze moved, at last, to the Fallen. A young girl, black-haired, olive-skinned, sharp-featured, looking for all the world as if she’d just come from Marseilles or Montpellier. In the brief interval, her innate magic had had time to start healing the worst of her broken bones, though neither her wings nor the two fingers she’d lost would ever regrow. There were rules and boundaries set on the Fallen: the bitter cage of their existence on Earth that they all learned to live in.

“I heard from Madeleine,” Javier said. “She’s on her way with a couple helpers. Should be there in a couple minutes.”

“Good,” Selene said. “Go and prepare the car, will you?” She looked again at the young man, at the foreign features of his face. Annamites were a familiar sight in the city: they were citizens of France, after all, albeit, like all colonial subjects, second-rate ones. Emmanuelle, Selene’s lover, manifested as African; but Emmanuelle was a Fallen who had never left Paris in her life. Whatever the young man was, he was not and had never been a Fallen.

“As you wish,” Javier said. “I’ll send you the helpers to pick her up.”

Selene shook her head. “Not just her. We’ll have two passengers this time, Javier.”

She didn’t know what the young man was, but she most definitely intended to find out.

Excerpted from The House of Shattered Wings © Aliette de Bodard, 2015